In this post it will be discussed J.B. Priest’s method of time treating in his plays and books. To have an idea what he thought about methaphysics of Time, please take a look at One Man and Time, speculations and case studies.

After an extensive discussion about how the creations of his most famous plays occurred, Priestley came up about the following theory, and I quote:

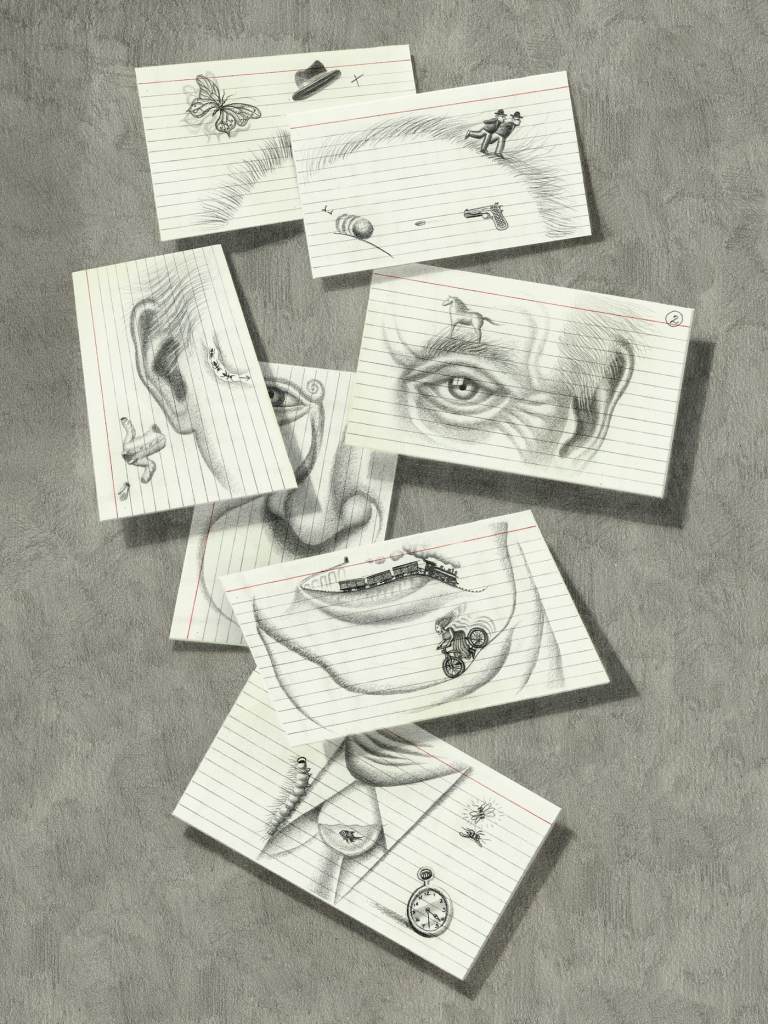

Time seems to divide itself into times:

- There is one for passing time;

- there is another for the first kind of experience, the contemplative slower-up;

- there is another for the second kind of experience, the purposeful, imaginative, creative speeder-up: three times.

So can it be true to say that nothing in our actual experience suggests – if we want to be geometrical about it – that there might be three dimensions of Time? I say it cannot be true. I will agree that no exact analysis may be possible, that no sharp lines can be drawn, that all except one’s innermost feeling is blurred and shadowy, that the relation between consciousness and the unconscious may complicate the issue; but I cannot escape the feeling that Time, itself so blurred and vague and elusive, divides itself into three to match these different modes of consciousness. We are at least entitled to say that it is as if there are three kinds of time. (And this is hardly an impudent claim when Time itself, on close examination, can be turned into an as if, even though we have in this age transformed it into a ball-and-chain to keep the spirit a prisoner.)

At the risk of appearing to put myself too close to Dunne, I propose to call these three times— time One, time Two, and time Three. To follow some theorists and call time Two “eternity,” a term rich in associations, would only mislead and confuse many readers. Again, though it would not be difficult to invent a name for time Three – like Mr. Bennett’s “Hyparxis”—some of us are easily repelled by unfamiliar terms. So let us make do with times One, Two, and Three, remembering that we live in all three of them at once, though we may not enjoy, so to speak, equal portions of them.

As visible creatures of earth we are ruled by time One.

We are born into it, grow up and grow old in it, and die in it. Our brains have developed through eons into marvelous instruments of time-One attention. Not only do they bring to our notice almost everything we feel we ought to know, but they are able to exclude what might be bewildering and unhelpful. When drugs interfere with their chemistry, some of their inhibiting processes do not work, and then we might see a chair as a Van Gogh might see it, not as a furniture salesman and a customer might see it. (The Time-shift in drug experiences is well attested; they free consciousness from its age-old concentration upon time one).

Our relation through the brain with time One tends to be practical and economic, good for our matter-handling business, which helps to explain why we are now great time-One people and mostly try not to believe in anything else. If this limited belief were imposed on people as a dogma, as it easily might be in totalitarian or severely conformist societies, it is not merely fanciful to suggest that men might become automata, ruled by better machines than themselves.

There are signs, however, of a reaction against this time-One dogma. Many of them have come my way since I began writing this book. Not all the forms this reaction takes are acceptable. One that is acceptable, concerned with all the extra sensory perception phenomena, ESP at work, which only sheer bigotry can deny now, seems to me outside the scope of this inquiry. But as we have seen already, even though we ignore all manner of examples of premonition and déjà vu experiences, there are plenty of authenticated precognitive dreams to prove that our minds cannot be entirely contained within time One. So let us take an early example of the precognitive dream, one connected with an historical event, and see what we can make of it in terms of more times than One.

Three months before Napoleon invaded Russia, the wife of General Toutschkoff had a dream that was repeated a second and then a third time in one night. In this dream she was in an inn she had never seen before, in some town she did not know, and her father came into the room, leading her small son by the hand, and told her in broken tones that her happiness was at an end because her husband had fallen at Borodino. She awoke in great distress, roused her husband, and asked him where Borodino was. But when they looked for the name on the map, they could not find it. (The battle in fact took its name from an obscure village.) After it was fought, everything happened as in the three dreams: She found herself in the same room in the same inn in the same town, and her father came in with her son and announced her husband’s death at Borodino, where he was commanding the army of the reserve.

More or less following Dunne here, we can say that the dreaming self of Countess Toutschkoff, in time Two, revealed what would happen to her in time One. Though a soldier’s wife might always be haunted by the fear that her husband might be killed in battle, coincidence must be ruled out of her three dreams because what happened was identical in so many different particulars and that the very name afterward given to the battle was then unknown to her. If no part of her mind could escape from time One, then the whole matter remains inexplicable.

Time Two

Another Time order, which we can call time Two, does at least offer us a possible explanation. But what about the historical event, the Battle of Borodino? Are we to assume that before Napoleon’s army crossed the Niemen on June 24, the Battle of Borodino on September 7 was already waiting to take its place in history? And if it was not, as we cannot help feeling, if it all depended on the calculations of the French and Russian general staffs and the consequences of various minor battles and skirmishes, then where did the dreamer’s mind, wandering in time Two, discover this unknown name Borodino? If in our instinctive dislike of the idea of a fixed unalterable future, we declare that early in June 1812, when the Countess dreamed her three dreams, events that were to take place in September did not exist in any possible shape or form, then how could she dream as she did? And if we accept her precognition, and with it the idea that this was an experience in time Two, impossible in time One, then how do we avoid the fixed future, the Borodino already in its place further along the track of time One? Before I try to answer those questions, let us return to the dream of the American mother about the visit to the creek and the dead baby (page 225):

What follows now does not come from my own collection but from an article on “Precognition and Intervention” by Dr. Louisa E. Rhine, published in the American Journal of Parapsychology:

Many years ago when my son, who is now a man with a baby a year old, was a boy I had a dream early one morning. I thought the children and I had gone camping with some friends. We were camped in such a pretty little glade on the shores of the sound between two hills. It was wooded, and our tents were under the trees. I looked around and thought what a lovely spot it was.

I thought I had some washing to do for the baby, so I went to the creek where it broadened out a little. There was a nice clean gravel spot, so I put the baby and the clothes down. I noticed I had forgotten the soap so I started back to the tent. The baby stood near the creek throwing handfuls of pebbles into the water. I got my soap and came back, and my baby was lying face down in the water. I pulled him out but he was dead. I awakened then, sobbing and crying. What a wave of joy went over me when I realized that I was safe in bed and that he was alive.

I thought about it and worried for a few days, but nothing happened and I forgot about it.

During that summer some friends asked the children and me to go camping with them. We cruised along the sound until we found a good place for our camp near fresh water. The lovely little glade between the hills had a small creek and big trees to pitch our tents under. While sitting on the beach with one of the other women watching the children play one day, I happened to think I had some washing to do, so I took the baby and went to the tent for the clothes. When I got back to the creek I put down the baby and the clothes, and then I noticed that I had forgotten the soap. I started back for it, and as I did so, the baby picked up a handful of pebbles and threw them in the water. Instantly my dream flashed into my mind. It was like a moving picture. He stood just as he had in my dream—white dress, yellow curls, shining sun. For a moment I almost collapsed. Then I caught him up and went back to the beach and my friends. When I composed myself, I told them about it. They just laughed and I said I imagined it. That is such a simple answer when one cannot give a good explanation. I am not given to imagining wild things.

After describing that dream, I said that if we accepted it, we must also accept one of two things:

- We must believe that up to the moment when the mother leaves the baby to go and fetch the soap, the dream is showing her the future, but that her return to find the baby drowned is a dramatization of not unusual maternal anxiety: the dream being therefore part-future, part-fiction.

- Or we must believe that a future containing a dead baby is changed, by the mother’s action, into a future in which the baby does not die and lives to become a father himself:

so that of two possibilities, one by deliberate intervention has come to be actualized. This leaves us with a future already existing so that it can be discovered by one part of the mind, and with a future that can be shaped by the exercise of our free will. We cannot have both, we shall be told; it must be either one or the other. Possibly, possibly not.

It may be remembered that I offered a similar alternative after an account of a motorist who dreamed that he knocked down a small boy and then, a few weeks afterward, had to swerve and brake violently to avoid hitting a small boy whom he immediately recognized, after getting out of his car, as the child he saw in his dream. I said that this dream could be part prevision, part fiction, or that it could show a possibility never actualized because the driver, forewarned by the dream, was able to act promptly at the right moment, changing the future seen in his dream.

In both instances, then, we are left with a choice: between a dream that only in part reveals the future and a dream entirely concerned with the future—but a future that is not fixed and inevitable, that can be changed. Let us consider the latter first. We are asked to accept a future that exists in some form or other, because it can be experienced in a dream, and yet may possibly be changed. Thinking theoretically, we feel inclined to reject at once any such idea of the future. Either the future is an “uncreated nothing” or it is wholly there, waiting for us to experience it. But this is only what we think in terms of Time theory.

In our ordinary thinking, outside theory and well inside practical living, not only do we not reject this idea of a half-made future, consisting of possibilities that may or may not be actualized – that is, becoming part of our and the world’s physical history – but we accept it so wholeheartedly that it shapes and colors our thought. When we think of the next 12 months we regard them neither as a blank nothing nor as some inflexible series of events. These extreme alternatives belong to theory, not to our actual practice, in which we do not hesitate to steer a course between them.

It is this intellectually infuriating future, rather like an omelette just before it is ready to be lifted out, that we hold in our minds when we are actually planning our lives and not picking and choosing among Time theories. Certainly an H-bomb missile may arrive and blow us all out of time One, but we are well aware of that, know that it is one of the possibilities that may be actualized. That missile, we may say, is waiting to be sent on its dreadful errand, to mark a high point of human folly; but it has been put together by man’s will and action and it can be outlawed and destroyed by man’s will and action. The future cannot be nothing, for it contains immediately, among other things, that missile; but neither is it fixed and inevitable, for it can be changed even after it has seemed to reveal itself in dreams and time Two.

It is then not at all outrageous to suggest that these two dreamers saw a future that existed in some shape or other (notice how we like saying, with Wells, “The shape of things to come”) and yet could be dramatically changed by a sudden act of will—the picking up of the baby, or the swerving and braking of the car. After all, it is far closer to our common working idea of the future -half-made, half-there, not wholly made or wholly there—than any conclusions of the scientists or the philosophers. We have in these dreams possibilities that were actualized namely, the visit to the creek, the encounter with the boy on the road and possibilities that were prevented from being actualized-namely, the drowning of the baby, the knocking down of the boy. (With the Borodino dream, of course, every thing was actualized, probably because an event on that scale, a great battle, is fixed beyond intervention.)

Now in time Two, where the dreams belong, there is no distinction between the possibilities that are actualized and those that are not. The creek and the road are there, and so are the drowned baby and the knocked-down boy. In time One, action can be taken so that what we might call the line of history avoids the drowned baby, the injured boy. But that is all. The alternative possibilities, together with the choice between them, cannot exist in time One. Nor did they exist in time Two. Therefore another time is necessary, time Three.

If we think of this line of material history really as a line, then as one possibility is actualized and others are not, this line cannot move up and down in two dimensions but must curve around in three. So on this theory of the two dreams we can accept Ouspensky‘s “The three-dimensionality of time is completely analogous to the three dimensionality of space” and J. G. Bennett’s “This leads to the notion of a third kind of time connected in some way with the power to connect or disconnect potential and actual.” And certainly, taking the baby away from the creek, swerving and braking to avoid the small boy on the road, may be said to be disconnecting potential and actual.

I refuse to answer questions, however, about these possibilities in time Three, these shapes of possible things to come, which can be seen in time Two and yet, until actualized, are outside our material history in time One. I refuse to answer because I do not know. Nobody should be surprised by this confession. After all I do not know, can only hazard a guess, how the sight of a picture or even the sound of a word could suddenly seem to change the tempo and tone of my existence, apparently taking me out of one time and enclosing me within another. I do not know, and again can only hazard a guess, how I came to write, let us say, the technically complicated Act Two of Time and the Conways seemingly without effort and at a headlong pace. All that is within my sure knowledge is that these things happened. But then every other day something happens that a positivist would call a coincidence and that I feel is nothing of the sort, though I cannot explain it. I am old enough now to realize how little I do know.

Let us see now what happens—and here I have little more advanced information than the reader has—when we reject the idea that these dreams were entirely concerned with the future, but a future that could be changed. We put in its place the idea that these dreams were, as I said earlier, part-future, part-fiction. The visit to the creek with the baby, in the dream, is a genuine time Two glimpse of the future, but the tragic episode of the baby’s death does not belong to the future but is, as I said, “a dramatization of not unusual maternal anxiety,” the kind of thing most women cannot help imagining

In the same way, that section of road and the small boy on it were there in the future, seen by the dreamer in time Two; but projected into the scene, out of the motorist’s constant anxiety about accidents, was the imaginary episode of injuring the boy. In these terms the future remains unchanged; all that happens is that what was imagined did not take place in reality. And at first sight this seems a much neater and more sensible explanation.

After reflection, however, this explanation leaves me feeling dissatisfied. The questions that seem to vanish have merely been swept away like crumbs and ash under a rug. Anxiety dreams are common enough; most of us have awakened to vaguely remember those dream airplanes and trains that will not be caught because taxis break down and luggage is mislaid. But in these two dreams there is no such dim confusion. As in most precognitive dreams, everything is sharp and clear, so vivid that it is easily remembered. And there does not appear to have been any break, any change of quality, between what was previsionary, disclosing the scene and the situation, and what belonged to a dramatized anxiety. The dead baby seems to have been as convincing as the live baby.

However, I do not wish to attack the theory from this position, if only because so much is possible in dreams, those vast private theatres in which we are dramatists, directors, designers, actors, and audience. (Long before I was interested in precognition, before I had read any depth psychology, I could not understand why so many people thought their dreams no more important than their sneezes and yawns. Our dreams are our nightlife.) I will suppose it to be true that a dream can move smoothly from prevision or precognition, from what is revealed, not created, to this familiar acting out of an anxiety or constant fear. Nevertheless, I am still left feeling dissatisfied.

Certainly we have now dodged the future that can be experienced and yet changed, and those possibilities that may or may not be actualized. It is much easier to say that something was imagined—such as the death of the baby—that did not subsequently take place in reality. It is easier still if we assume, as so many people seem to do, that the imagination and all its creations are nothing. But this will not do, for these are very much something, and something of immense importance to our lives. (What if we should finally arrive, a long way beyond death, at a mode of existence that remained nothing but a huge blank unless the imagination went to work on it, creating for it landscapes, cities, dwellings, gardens, arts, and social life?)

Because most children are highly imaginative, it is supposed by some that to reach maturity we ought to leave imagination behind, like the habit of smearing our faces with jam or chocolate. But an adult in whom imagination has withered is mentally lame and lopsided, in danger of turning into a zombie or a murderer. It is the creative imagination that has given our ruthless blood thirsty species its occasional gleams of nobility, its hope of rising above the muck it spreads.

To discover what we make of imagination I am consulting the nearest Dictionary of Philosophy, an unambitious American work, usefully modest in size. It says:

Imagination designates a mental process consisting of:

- (a) The revival of sense images derived from earlier perceptions (the reproductive imagination), and

- (b) the combination of these elementary images into new units (the creative or productive imagination).

The creative imagination is of two kinds:

- (a) the fancy which is relatively spontaneous and uncontrolled, and

- (b) the constructive imagination, exemplified in science, invention and philosophy which is controlled by a dominant plan or purpose.

To which I feel I must reply:

- (a) that there is here a smell of the cobbler’s “Nothing like leather”;

- (b) that I should like to read the comments of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Blake on this account of imagination;

- (c) that the enduring vitality, say, of Don Quixote and Hamlet, apparently the products of uncontrolled fancy, is not easy to explain along these lines; and

- (d) that if this can be taken as a representative statement, then we know and care very little about imagination. It really belongs to the invisible nothing department.

Because imagination appears to be free of the limitations we know in time One, we think of it as being outside Time. It is there, however, that the nothings begin. We might do better if we thought of it as belonging to a different Time order, to another time. And I have already suggested, after remembering my own experience, that imaginative creation seems to imply not a second time order, contemplative and detached from action, but a third, in which purpose and action are joined together and there seems to be an almost magical release of creative power.

If there is a part of the mind or a state of consciousness that is outside the dominion of time One and time Two but is governed by a time Three, then that is where the creative imagination has its home and does its work. And it may be that there imagination is not something escaping from reality but is itself reality, while the world we construct from our time-One experience is regarded there as something artificial, abstract, thin, and hollow.

Now what belonged to the time-One future in these two dreams, the baby at the creek, the small boy on the road, could only be observed in the wide but badly focused present (compare Dunne) of time Two. This is what the dreamers are attending to, being asleep and incapable of concentrating their attention in time One. Now we are still assuming that the main incidents of the dreams, the death of the deserted baby, the running-down of the small boy, are not part of the future revealed in time Two. These tragic incidents have been neatly introduced into the dreams, perhaps to serve as warnings, by the dreamers hastily dramatizing familiar anxieties. Thus the set and the characters are provided by future experience, but the action comes out of imagination. This is all very curious, but it is what we must accept in this theory of dreams.

And Time cannot be left out, because we know the future is involved; and if Time is in, then it cannot be uni-dimensional, for we need another and different time, a time Two, to explain how the future came to be revealed. But this will not explain what we have already assumed: the sudden change in the character of the dreams, the switch-over from prevision to imagination, the dramatic intervention of the dreamers’ anxieties and fears.

In which time order did imagination come to intervene? Not in time One, which is closed down for the night. Not in time Two, which is concerned with the time One future and is providing the baby at the creek and the small boy on the road. The dramas, the warning strokes of the imagination, which will eventually produce decisive actions in time One, must belong neither to time One nor time Two but to time Three. So, trhough by a very different route, we arrive again at that third dimension of Time.

Time Three

Nevertheless, I prefer the other explanation of these dreams, which does not see them as a mixture of prevision and imagination (even though we do not know what imagination is) but as glimpses of a future already shaped but still pliable, yielding—in these instances, though obviously not in many others—to will and action. It is as if ahead of us in time One were shapes, molds, patterns, possibilities, seen as definite events in certain of our dreams; and into some of these shapes, molds, patterns, there arrives the material substance that actualizes them, hardening them into world history. There is an idea not unlike this in Blake’s Jerusalem, in which Los (the name is Sol reversed) can be taken as the symbolic figure of Time:

All things acted on Earth are seen in the bright Sculptures of Los's Halls, & every Age renews its powers from these Works With every pathetic story possible to happen from Hate or Wayward Love; & every sorrow & distress is carved here, Every Affinity of Parents, Marriages & Friendships are here In all their various combinations wrought with wondrous Art, All that can happen to Man in his pilgrimage of seventy years...

These “Sculptures,” as Maurice Nicoll suggested, can be regarded as states of mind from which men cannot free themselves; but they can also be seen as the possibilities, like the Borodino of the Countess’s dream, that must be actualized. They are that part of the future that is fixed. But much of it, close to us as individuals, is only half made, depending for its historical time-One shape and character on a number of personal decisions.

This brings us to the questions I asked at the end of the chapter “The Dreams.” There, after pointing out that more than 90 per cent of the precognitive dreams I was sent were concerned with the terrible or the trivial, I asked why the dreaming self so rarely catches a glimpse of that wide middle range of our activities and interests. And now we can reply that within this range there may so often be no determined future, only a confusion of possibilities still to be actualized, waiting to receive their time-One shape and character from will and action. Both the terrible and the trivial are nearly always outside our control, the deaths and disasters because they are too big and fateful, the trivia because they are too small and unimportant. So that it is they in nine cases out of 10, at least, that will be revealed in precognitive dreams because they are there to be revealed. These possibilities are part of the future that will not be changed, either because they are out of reach of our will or beneath its attention and interest.

Along this line we can now approach the FIP (future-influencing-present) effect. Why did my friend Dr. A feel a queer excitement when he received impersonal official reports from Mrs. B, then completely unknown to him? His consciousness in time One knew nothing about her. No dreams from time Two visited him. But in time Three they had already fallen in love and were married. This deep relationship, for some reason I cannot supply, was not a possibility but a certainty, but only in that remoter part of his being – if I may be allowed the phrase involved with time Three, able to communicate nothing to his time One consciousness but this queer feeling of excitement.

This is no doubt an exceptional instance, but what is not at all rare, at least in my experience, is a state of mind suddenly and inexplicably illuminated or darkened by feelings apparently coming from nowhere and entirely unconcerned with what we are doing, thinking, feeling, in our time One existence. This last rightly demands most of our attention, but we must not make the mistake of assuming that anything not explicable in time One terms is a nothing. It may be a very important something, like the excitement that Dr. A felt, the distant trumpets heralding the most rewarding relationship of his life. We should think a man a fool if he insisted upon meeting all his time-One experience with half closed eyes and with wax pads over his ears. we shall not be very much wiser if, to prove narrow a theory, we try to keep our minds clo to what might be revealed to them in it.

I have lately received, from Italy, some material based on the findings and theorizing of a small newish international group of medical psychologists. This restored to me a term much used before the First War, when I first began read about and discussing such matters, but one have rarely seen or heard since then: This is “superconscious.” On this theory the ego and field of consciousness occupies a middle place between the unconscious, personal or collective and the superconscious, the source of our nobler feelings, intuitions and inspiration, genius illumination, and ecstasy.

And if we relate this division to our tempo system here, we could say that the ego and field of consciousness belong to time One, the unconscious to time Two, the superconscious to time Three. But we must remember there are no separate compartments and exact divisions and that we live, even here and now, in all three times. This still remains true even of those people who deny the possibility of any experience outside side time One. However, it may not always be true, for if we insist upon disinheriting ourselves, men may ultimately become time One slaves automata.

I have said that we go beyond the grave. But one sense and strictly speaking, we do not. Indeed, it is the idea of a time-One existence persisting after death that has worked so much mischief. It has helped to create some of the dreariest fantasies ever known, with the spirits of departed Red Indians arriving in South London basements to establish communications between this world and the next. It has so repelled many people that they proclaim with passion that long before the doctor has signed his certificate shall be dead as mutton. The truth is, we are a to be immodest in both our claims and our denials here: Either we live for ever or perish with our last heartbeat. I think it reasonable to suggest we do neither. We are not demigods and we are not cattle.

We cannot go beyond the grave in time One. When we die we come to the end of our allotment of time One. The brain ceases to supply us with any further information because it stops working, dying with the body that housed it. We have to take our leave of chronological world time. We move out of history: Thou thy worldly task hast done, Home art gone, and ta’en thy wages.

But where is home, and what are our wages? In terms of our argument here, we can say that home is our continued existence in time Two and that our wages, there for us to spend in that existence, are our total experience in time One. This has an end just as it had a beginning in time One; we go jogging along that world line until death appears as a terminus; but in time Two we have never been making that journey and, as we have seen, have never been bound by its conditions. There may be some kind of death awaiting us ultimately in time Two, but it is certainly not the familiar time-One death. This we survive because our consciousness has never been contained within time One.

And it is quite beside the point to object that we have no visible evidence to prove that survival. Time Two, in which we do survive, does not work in the visible-evidence department. I cannot take that “aesthetic feeling,” a time-Two experience, into a laboratory to be weighed and measured. The most meaningful and the most ecstatic moment I have ever known occurred in a dream, not precognitive but deeply symbolic, a dream that changed my whole outlook; yet I have for it less visible evidence than I have for a slight cold in the head or a broken fingernail.

Our time-Two world, in which we survive, has as its foundation our total experience in time One. Now it cannot be denied, for this has been proved over and over again, that the brain acts as a marvelous recording instrument, storing somehow and somewhere an exact impression of every moment of our lives, something quite different, in its brilliant immediacy, from what may be recovered by the ordinary memory. (Under hypnosis or the emotional pressure of drastic analysis, middle-aged men and women have been suddenly turned back into children of two, destructive and screaming with rage.) What the relations are between this stupendous brain storehouse and the mind or consciousness and the unconscious, I do not know, and I do not think anybody else knows.

And I am not denying that this endless recording, much of it inaccessible to our day-by-day consciousness and seemingly out of all proportion to our needs, may play a part, not yet understood, in our time – One existence.

But I believe with Dunne that when we have come to an end in time One, we go forward spatially and geometrically, we may say, at a right angle—in time Two, no longer concentrating our attention on the physical world, but now having in place of it all that accumulation of mental events, all the sensations, feelings, thoughts, left to us from our time-One lives. It must be remembered, however, that we have never been living exclusively in time One, however much we may proclaim that no other time exists. So it might be as well for us hereafter, when we are out of passing time, that we do not think and feel and behave now as if passing time were all we had. And surely this is what most religions, behind their popular melodramas of angels and demons, saviors and devils, heavens and hells, have been trying to teach us.

Because we have never been living exclusively in time One, we are not without clues—that is, if we do not willfully ignore them—as to what might happen when we are no longer in passing time. I have already given some examples of what we might call time-Two and time-Three effects, taken from my own experience. Now here is another. Can we imagine ourselves in a fifth dimension (time Two) obtaining a four dimensional impression of a fellow creature? Alarmed by these dimensions, about to create a monster, we will probably reply at once that we cannot even imagine such an impression. But unless we have been unlucky in our relationships, I maintain that we are always taking what is in effect a four-dimensional view of the persons nearest and dearest to us. It is in fact impossible to avoid taking this view in a close, deep, and lasting relationship.

We do not see these loved persons entirely in passing time, as three-dimensional cross-sections of their real selves. We habitually see them, somewhat out of focus in passing time, in a curious blur that releases tenderness, not only as they are but also as they might be and as they were, reaching back, if we are parents, to their earliest childhood. The eagerness of lovers—and this is especially true of most women, usually more aware of this four-dimensional effect than most men—to know, to see, what the other was like years before they met, seems part of an instinctive desire to enjoy this deeper impression as soon as possible. It is an attempt, inspired by profound emotion, to reach beyond passing time, to fix the relationship in different and more enduring conditions of experience.

Then dreams, of course, offer us other clues as to what might happen when we are no longer in time One. This does not mean that dreams in general—and now we set apart those rare clear dreams can be taken as examples of our time Two existence. Allowance must be made, as Dunne pointed out, for the confusion between two times, two outlooks. When we no longer return to time One, the situation is altered. (But there is a Buddhist tradition that a man who can control his dreams while dreaming will control his states of being in the after life.) We shall have to learn how to live in time Two, which might well seem at first an uncontrollable dream world, through which our consciousness wanders like Alice on the other side of the looking glass. Because, as in dreams, we can no longer know certain time intensities, we shall miss the keenest sensual satisfactions but we shall also be beyond the reach of the sharpest pain. On the other hand, again as in dreams, what might be called our emotional landscape may be immensely enlarged and far more highly colored, mountains of wonder and joy rising above sinister depths and chasms of terror.

Any notion that wish fulfillment is at work here, sketching this time-Two and time-Three existence beyond time One in soft pastel shades, can be dismissed at once. We shall not sink into Abraham’s or anybody else’s bosom. We shall not be little lambs gently carried into the fold. The last flicker of our time-One consciousness will not cancel out for ever our follies and malignities, allowing us the sleep of the just when we have been so unjust. (Because so many people believe or hope it will, they no longer feel responsible.) It is here, in the world we have made, we really begin to live with ourselves,” and reap between these heavenly heights and hellish depths what we have sown. And we can not say we have not been warned; we have been warned over and over and over again.

Anybody who can find wish fulfillment here must feel a great deal more complacent about his time-One life that I do about mine. I can see this time-Two existence, with time Three and its fiery creative energies now a new time Two, offering us some very rough going. Courage, imagination, and love, which we praise in a routine fashion more often than we really try to achieve, may be as urgently necessary as air and water and bread are now. So we might be well advised to stock up while we can. (It is what we were always told to do—that is, before we became members of an affluent super-technological society, giddy with conceit because we might put a man on the moon.)

There is, however, one feature of this time Two after-life that might seem to suggest a kind of professional wish fulfillment on my part. For I am by profession and temperament a dramatist, and I detest ill-contrived and under rehearsed scenes. But my time – One life can show me—and indeed will show me when it turns into my time-Two world – far too many of such scenes. So I welcome the chance not of simply re-living them, though that may have to be done, but of beginning to put them right. For this I believe, quite apart from any professional and temperamental bias, we shall have an opportunity of doing, if we can work with others, whose lines cross ours in this time-Two world, in trust and love. We may have the choice—and this involves no intervention from higher levels of being; the choice could be entirely ours—between building a self-glorifying palace out of our time-One material, until we wall ourselves into a hell of loneliness and desolation, and trying to create in trust and love, at what we might call the crossroads of our respective world lines, a new and more rewarding life. We can begin to do this here and now. But we can do it better there, on the other side of that first but not last curtain of Time.

Even while we are on this side of that curtain, however, is there not always a something else that can never be fitted into the time-One pattern? I am not thinking now about precognitive dreams, premonitions, and the like, nor about the contemplative-aesthetic and the imaginative-creative experiences I described earlier. This something else is impossible to prove and is hard to capture in words. It can come at high moments of love and, though rarely, at a meeting of friends; it can transform some sudden glimpse of a landscape into an irradiated sign; it haunts some music for us; its light and its strange shadows fall on certain scenes in drama and fiction. Always it adds depth to life, suggests an ampler Time, opens a new dimension.

It never stays long, at least for most of us, but if, fixed in our attention to time One, we cease to be conscious of this something else, this bonus from the unknown, really arriving from another mode of Time, we begin to feel stale and weary. We are not only not preparing ourselves for existence in the next world, we are beginning to lose interest even in this one, for the scene is flat and its colors are fading. To die is not to close our eyes when we come to the end of our time One: it is to choose to live in too few dimensions. My personal belief, then, is that our lives are not contained within passing time, a single track along which we hurry to oblivion. We exist in more than one dimension of Time. Ourselves in times Two and Three cannot vanish into the grave; they are already beyond it even now. We may not be immortal beings—I do not think we are or should want to be—but we are something better than creatures carried on that single time track to the slaughter-house. We have a larger portion of Time—and more and stranger adventures with it—than conventional or positivist thought allows.

But it is still a portion; we have not unlimited Time, though what the limits will be in time Two and time Three, I do not know. Nor of course do I know what happens. I suspect, however, that in time Two we begin by being more essentially ourselves than in time One but end by being less ourselves, personality as we know it vanishing altogether in time Three.

We are not demigods and we are not cattle. We are more than our brains but not in the end, I feel, more than the consciousness those brains exist to serve. There is in me something greater and more enduring than anything in my time One experience. But outside or beyond that experience, not in time One, is something infinitely greater and more enduring than anything I can claim as mine. This I realized in that dream or vision of the birds, which I described 25 years ago in Rain Upon Godshill, from which I shall quote it. The setting of the dream owed much to the fact that not long before, late at night, I had helped with some bird-ringing at the St. Catherine’s lighthouse in the Isle of Wight:

I dreamt I was standing at the top of a very high tower, alone, looking down upon myriads of birds all flying in one direction; every kind of bird was there, all the birds in the world. It was a noble sight, this vast aerial river of birds. But now in some mysterious fashion the gear was changed, and time speeded up, so that I saw generations of birds, watched them break their shells, flutter into life, weaken, falter, and die. Wings grew only to crumble; bodies were sleek and then, in a flash, bled and shrivelled; and death struck everywhere at every second. What was the use of all this blind struggle towards life, this eager trying of wings, all this gigantic meaningless biological effort? As I stared down, seeming to see every creature’s ignoble little history almost at a glance, I felt sick at heart. It would be better if not one of them, not one of us all, had been born, if the struggle ceased for ever. I stood on my tower, still alone, desperately unhappy. But now the gear was changed again and time went faster still, and it was rushing by at such a rate, that the birds could not show any movement but were like an enormous plain sown with feathers. But along this plain, flickering through the bodies themselves, there now passed a sort of white flame, trembling, dancing, then hurrying on; and as soon as I saw it I knew that this flame was life itself, the very quintessence of being; and then it came to me, in a rocket-burst of ecstasy, that nothing mattered, nothing could ever matter, because nothing else was real, but this quivering and hurrying lambency of being. Birds, men, or creatures not yet shaped and coloured, all were of no account except so far as this flame of life travelled through them. It left nothing to mourn over behind it; what I had thought was tragedy was mere emptiness or a shadow show; for now all real feeling was caught and purified and danced on ecstatically with the white flame of life. I had never felt before such deep happiness as I knew at the end of my dream of the tower and the birds….

And this white flame did not become visible, you may have noticed, until after the second speeding-up of all that bird life, in what could be described as the third time.

Readers of Jung will remember the importance he attaches to a process of development he calls “individuation,” which, bringing a new relation to the unconscious, transforms the one sided ego into the broadly-based “Self.” (Incidentally, he found a similar process and transformation, expressed symbolically, in ancient Chinese thought.)

Individuation =“the evolution of the psyche to its wholeness,” its way of maturing, in which the archetypes appear both as structural elements and as regulators of the unconscious psychic material and constitute particularly dynamic factors. The phases of this process are characterized by the confrontation of the conscious with some typical components of the unconscious realm (shadow, animus–anima, the great mother, the wise old man, the self, etc.). From the perspective of wholeness, which is always kept in mind, both the first and the second halves of life receive their appropriate significance.

Now this must be rarely achieved, and only then, in most instances, toward the end of a longish life. What, then, is the point of it? Why struggle toward a goal overshadowed by the grave? Why at last understand how to live just when you are about to stop living?

Jung neither asked nor answered such questions. But now I believe that his “individuation” and achievement of the “Self” are a preparation for existence outside time One, in times Two and Three. Probably in time Two we move from personality to the essential self, never realized in time One; and that now, in time Two, sooner or later the self must take on, as it were, its final shape and coloring, extending itself to its limits; perhaps those belonging to one of a small number of equally essential types. We must become more completely ourselves before, in our existence only in time Three, finally dissolving into selfless consciousness, as I appeared to do when ecstatically aware only of that white flame.

There is of course purpose in all this. I am not an atheist, but I cannot agree with men who talk about God as if He had once attended a Speech Day at their theological college. That hurrying, trembling, delicate, white flame was not God but it was numinous. We might say it was moving to and from unimaginable creative Being, both away from and toward a blinding Absolute, possibly through the history of a thousand million planets. For whatever else this universe might be, it is obviously very large and extremely complicated. It must therefore contain innumerable levels of being, about which we know no more than a beetle does about the proceedings of the British Association. We men on earth are probably on a very low level, but we have our task like other and higher orders of beings. As far as I can see—and I claim no prophetic insight—that task is to bring consciousness to the life of earth—or, as Jung wrote in his old age, “to kindle a light in the darkness of mere being.”

We cannot perform this service, just as we cannot even enjoy a good life, unless our minds and personalities are free to develop in their own fashion, outside the iron molds of totalitarian states and systems, narrow and authoritarian churches, and equally narrow and dogmatic scientific-positivist opinion. It happens that all three are bearing down on us now, so that while men have always lived in jeopardy, our present position is unusually precarious. We have now arrived at a complicated crossroads, where every turning but one—and that one the least obvious, no great roaring highway—will be disastrous.

I have written this book in the belief that the choice of the right turning, a decision that may be final if not for our whole species then at least for our civilization, cannot be separated from the relations between Man and Time.

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

Dante’s Inferno First Canto

Got to the third paragraph of

and from there to the discussion which should complement everything discussed here:

God does not play dice with the Universe

Inside this post I created a loop which intertwine what is reality with what is to think which with its kind of a stacked mobile definition which gives an idea of what is at stake.

Since my main objective is to discuss the point of view of the observer, I discuss also how we humans as observers develop